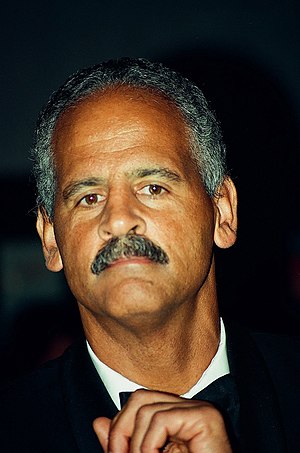

Francis Fukuyama height - How tall is Francis Fukuyama?

Francis Fukuyama was born on 27 October, 1952 in Hyde Park, Chicago, Illinois, United States, is an American political scientist, political economist, and author. At 68 years old, Francis Fukuyama height not available right now. We will update Francis Fukuyama's height soon as possible.

Now We discover Francis Fukuyama's Biography, Age, Physical Stats, Dating/Affairs, Family and career updates. Learn How rich is He in this year and how He spends money? Also learn how He earned most of net worth at the age of 70 years old?

| Popular As |

N/A |

| Occupation |

N/A |

| Francis Fukuyama Age |

70 years old |

| Zodiac Sign |

Scorpio |

| Born |

27 October 1952 |

| Birthday |

27 October |

| Birthplace |

Hyde Park, Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Nationality |

United States |

We recommend you to check the complete list of Famous People born on 27 October.

He is a member of famous Author with the age 70 years old group.

Francis Fukuyama Weight & Measurements

| Physical Status |

| Weight |

Not Available |

| Body Measurements |

Not Available |

| Eye Color |

Not Available |

| Hair Color |

Not Available |

Who Is Francis Fukuyama's Wife?

His wife is Laura Holmgren

| Family |

| Parents |

Not Available |

| Wife |

Laura Holmgren |

| Sibling |

Not Available |

| Children |

Not Available |

Francis Fukuyama Net Worth

He net worth has been growing significantly in 2021-22. So, how much is Francis Fukuyama worth at the age of 70 years old? Francis Fukuyama’s income source is mostly from being a successful Author. He is from United States. We have estimated

Francis Fukuyama's net worth

, money, salary, income, and assets.

| Net Worth in 2022 |

$1 Million - $5 Million |

| Salary in 2022 |

Under Review |

| Net Worth in 2021 |

Pending |

| Salary in 2021 |

Under Review |

| House |

Not Available |

| Cars |

Not Available |

| Source of Income |

Author |

Francis Fukuyama Social Network

Timeline

In a review for The Washington Post, Fukuyama discussed Ezra Klein's 2020 book Why We're Polarized regarding US politics, and outlined Klein's central conclusion about the importance of race and white identity to Donald Trump voters and Republicans.

His most recent book, published in 2018, is Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment.

In a 2018 interview with New Statesman, when asked about his views on the resurgence of socialist politics in the United States and the United Kingdom, he responded:

The 2014 book is the second book on political order, following the 2011 book The Origins of Political Order. In this book, Fukuyama covers events taking place since the French Revolution and shed light on political institutions and their development in different regions.

It all depends on what you mean by socialism. Ownership of the means of production – except in areas where it's clearly called for, like public utilities – I don't think that's going to work. If you mean redistributive programmes that try to redress this big imbalance in both incomes and wealth that has emerged then, yes, I think not only can it come back, it ought to come back. This extended period, which started with Reagan and Thatcher, in which a certain set of ideas about the benefits of unregulated markets took hold, in many ways it's had a disastrous effect. At this juncture, it seems to me that certain things Karl Marx said are turning out to be true. He talked about the crisis of overproduction… that workers would be impoverished and there would be insufficient demand.

In the 2011 book, Fukuyama describes what makes a state stable. It uses comparative political history to develop a theory of the stability of a political system. According to Fukuyama, an ideal political order needs a modern and effective state, the rule of law governing the state and be accountable.

Fukuyama has been a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies since July 2010 and a Mosbacher Director of the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University. In August 2019, he was named director of the Ford Dorsey Master's in International Policy at Stanford.

Fukuyama was the Omer L. and Nancy Hirst Professor of Public Policy in the School of Public Policy at George Mason University from 1996 to 2000. Until July 10, 2010, he was the Bernard L. Schwartz Professor of International Political Economy and Director of the International Development Program at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins University in Washington, D.C. He is now Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow and resident in the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University, and director of the Ford Dorsey Master's in International Policy at Stanford.

In 2008, Fukuyama published the book Falling Behind: Explaining the Development Gap Between Latin America and the United States, which resulted from research and a conference funded by Grupo Mayan to gain understanding on why Latin America, once far wealthier than North America, fell behind in terms of development in only a matter of centuries. Discussing this book at a 2009 conference, Fukuyama outlined his belief that inequality within Latin American nations is a key impediment to growth. An unequal distribution of wealth, he stated, leads to social upheaval, which then results in stunted growth.

Fukuyama endorsed Barack Obama in the 2008 US presidential election. He states:

In 2006, in America at the Crossroads, Fukuyama discusses the history of neoconservatism, with particular focus on its major tenets and political implications. He outlines his rationale for supporting the Bush administration, as well as where he believes it has gone wrong.

In a New York Times article from February 2006, Fukuyama, in considering the ongoing Iraq War, stated: "What American foreign policy needs is not a return to a narrow and cynical realism, but rather the formulation of a 'realistic Wilsonianism' that better matches means to ends." In regard to neoconservatism, he went on to say: "What is needed now are new ideas, neither neoconservative nor realist, for how America is to relate to the rest of the world – ideas that retain the neoconservative belief in the universality of human rights, but without its illusions about the efficacy of American power and hegemony to bring these ends about."

The US should instead stimulate political and economic development and gain a better understanding of what happens in other countries. The best instruments are setting a good example and providing education and, in many cases, money. The secret of development, be it political or economic, is that it never comes from outsiders, but always from people in the country itself. One thing the US proved to have excelled in during the aftermath of World War II was the formation of international institutions. A return to support for these structures would combine American power with international legitimacy, but such measures require a lot of patience. This is the central thesis of his 2006 work America at the Crossroads.

In a 2006 essay in The New York Times Magazine strongly critical of the invasion, he identified neoconservatism with Leninism. He wrote that neoconservatives:

At an annual dinner of the American Enterprise Institute in February 2004, Dick Cheney and Charles Krauthammer declared the beginning of a unipolar era under American hegemony. "All of these people around me were cheering wildly," Fukuyama remembers. He believes that the Iraq War was being blundered. "All of my friends had taken leave of reality." He has not spoken to Paul Wolfowitz (previously a good friend) since.

Fukuyama began to distance himself from the neoconservative agenda of the Bush administration, citing its excessive militarism and embrace of unilateral armed intervention, particularly in the Middle East. By late 2003, Fukuyama had voiced his growing opposition to the Iraq War and called for Donald Rumsfeld's resignation as Secretary of Defense.

As a key Reagan Administration contributor to the formulation of the Reagan Doctrine, Fukuyama is an important figure in the rise of neoconservatism, although his works came out years after Irving Kristol's 1972 book crystallized neoconservatism. Fukuyama was active in the Project for the New American Century think tank starting in 1997, and as a member co-signed the organization's 1998 letter recommending that President Bill Clinton support Iraqi insurgencies in the overthrow of then-President of Iraq Saddam Hussein. He was also among forty co-signers of William Kristol's September 20, 2001 letter to President George W. Bush after the September 11, 2001 attacks that suggested the U.S. not only "capture or kill Osama bin Laden", but also embark upon "a determined effort to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq".

Authors like Ralf Dahrendorf argued in 1990 that the essay gave Fukuyama his 15 minutes of fame, which will be followed by a slide into obscurity. He continued to remain a relevant and cited public intellectual leading American communitarian Amitai Etzioni to declare him "one of the few enduring public intellectuals. They are often media stars who are eaten up and spat out after their 15 minutes. But he has lasted."

Fukuyama is best known as the author of The End of History and the Last Man, in which he argued that the progression of human history as a struggle between ideologies is largely at an end, with the world settling on liberal democracy after the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Fukuyama predicted the eventual global triumph of political and economic liberalism:

Fukuyama received his Bachelor of Arts degree in classics from Cornell University, where he studied political philosophy under Allan Bloom. He initially pursued graduate studies in comparative literature at Yale University, going to Paris for six months to study under Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida but became disillusioned and switched to political science at Harvard University. There, he studied with Samuel P. Huntington and Harvey Mansfield, among others. He earned his Ph.D. in political science at Harvard for his thesis on Soviet threats to intervene in the Middle East. In 1979, he joined the global policy think tank RAND Corporation.

Yoshihiro Francis Fukuyama (/ˌ f uː k uː ˈ j ɑː m ə , -k ə ˈ -/ , Japanese: [ɸɯ̥kɯꜜjama] ; born October 27, 1952) is an American political scientist, political economist, and writer. Fukuyama is known for his book The End of History and the Last Man (1992), which argued that the worldwide spread of liberal democracies and free-market capitalism of the West and its lifestyle may signal the end point of humanity's sociocultural evolution and become the final form of human government. However, his subsequent book Trust: Social Virtues and Creation of Prosperity (1995) modified his earlier position to acknowledge that culture cannot be cleanly separated from economics. Fukuyama is also associated with the rise of the neoconservative movement, from which he has since distanced himself.

Francis Fukuyama was born in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois, United States. His paternal grandfather fled the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 and started a shop on the west coast before being interned in the Second World War. His father, Yoshio Fukuyama (福山喜雄 ), a second-generation Japanese American, was trained as a minister in the Congregational Church, received a doctorate in sociology from the University of Chicago, and taught religious studies. His mother, Toshiko Kawata Fukuyama (河田敏子 ), was born in Kyoto, Japan, and was the daughter of Shiro Kawata (河田嗣郎 ), founder of the Economics Department of Kyoto University and first president of Osaka City University. Francis grew up in Manhattan as an only child, had little contact with Japanese culture, and did not learn Japanese. His family moved to State College, Pennsylvania, in 1967.