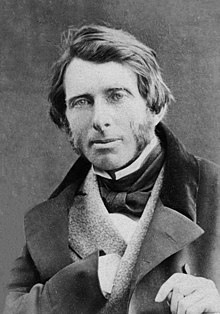

John Ruskin height - How tall is John Ruskin?

John Ruskin was born on 8 February, 1819 in Brunswick Square, is a 19th-century English writer and art critic. At 81 years old, John Ruskin height is 5 ft 10 in (178.0 cm).

-

5' 10"

-

6' 0"

-

6' 2"

-

6' 3"

-

6' 2"

Now We discover John Ruskin's Biography, Age, Physical Stats, Dating/Affairs, Family and career updates. Learn How rich is He in this year and how He spends money? Also learn how He earned most of net worth at the age of 81 years old?

| Popular As |

N/A |

| Occupation |

writer |

| John Ruskin Age |

81 years old |

| Zodiac Sign |

Aquarius |

| Born |

8 February 1819 |

| Birthday |

8 February |

| Birthplace |

Brunswick Square |

| Date of death |

January 20, 1900 |

| Died Place |

Brantwood, United Kingdom |

| Nationality |

Brunswick Square |

We recommend you to check the complete list of Famous People born on 8 February.

He is a member of famous Writer with the age 81 years old group.

John Ruskin Weight & Measurements

| Physical Status |

| Weight |

Not Available |

| Body Measurements |

Not Available |

| Eye Color |

Not Available |

| Hair Color |

Not Available |

Who Is John Ruskin's Wife?

His wife is Effie Gray (m. 1848–1854)

| Family |

| Parents |

Not Available |

| Wife |

Effie Gray (m. 1848–1854) |

| Sibling |

Not Available |

| Children |

Not Available |

John Ruskin Net Worth

He net worth has been growing significantly in 2021-22. So, how much is John Ruskin worth at the age of 81 years old? John Ruskin’s income source is mostly from being a successful Writer. He is from Brunswick Square. We have estimated

John Ruskin's net worth

, money, salary, income, and assets.

| Net Worth in 2022 |

$1 Million - $5 Million |

| Salary in 2022 |

Under Review |

| Net Worth in 2021 |

Pending |

| Salary in 2021 |

Under Review |

| House |

Not Available |

| Cars |

Not Available |

| Source of Income |

Writer |

John Ruskin Social Network

Timeline

[Ruskin’s] election to the second term of the Slade professorship took place in 1884, and he was announced to lecture at the Science Schools, by the park. I went off, never dreaming of difficulty about getting into any professorial lecture; but all the accesses were blocked, and finally I squeezed in between the Vice-Chancellor and his attendants as they forced a passage. All the young women in Oxford and all the girls’ schools had got in before us and filled the semi-circular auditorium. Every inch was crowded, and still no lecturer; and it was not apparent how he could arrive. Presently there was a commotion in the doorway, and over the heads and shoulders of tightly packed young men, a loose bundle was handed in and down the steps, till on the floor a small figure was deposited, which stood up and shook itself out, amused and good humoured, climbed on to the dais, spread out papers and began to read in a pleasant though fluting voice. Long hair, brown with grey through it; a soft brown beard, also streaked with grey; some loose kind of black garment (possibly to be described as a frock coat) with a master’s gown over it; loose baggy trousers, a thin gold chain round his neck with glass suspended, a lump of soft tie of some finely spun blue silk; and eyes much bluer than the tie: that was Ruskin as he came back to Oxford.

Ruskin's theories also inspired some architects to adapt the Gothic style. Such buildings created what has been called a distinctive "Ruskinian Gothic". Through his friendship with Henry Acland, Ruskin supported attempts to establish what became the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (designed by Benjamin Woodward)—which is the closest thing to a model of this style, but still failed to satisfy Ruskin completely. The many twists and turns in the Museum's development, not least its increasing cost, and the University authorities' less than enthusiastic attitude towards it, proved increasingly frustrating for Ruskin.

Will you – (it's all for your own good – !) make her stand up and then draw her for me without a cap – and, without her shoes, – (because of the heels) and without her mittens, and without her – frock and frills? And let me see exactly how tall she is – and – how – round. It will be so good of and for you – And to and for me.

Notable Ruskin enthusiasts include the writers Geoffrey Hill and Charles Tomlinson, and the politicians Patrick Cormack, Frank Judd, Frank Field and Tony Benn. In 2006, Chris Smith, Baron Smith of Finsbury, Raficq Abdulla, Jonathon Porritt and Nicholas Wright were among those to contribute to the symposium, There is no wealth but life: Ruskin in the 21st Century. Jonathan Glancey at The Guardian and Andrew Hill at the Financial Times have both written about Ruskin, as has the broadcaster Melvyn Bragg. In 2015, inspired by Ruskin's philosophy of education, Marc Turtletaub founded Meristem in Fair Oaks, California. The centre educates adolescents with developmental differences using Ruskin's "land and craft" ideals, transitioning them so they will succeed as adults in an evolving post-industrial society.

Until 2005, biographies of both J. M. W. Turner and Ruskin had claimed that in 1858 Ruskin burned bundles of erotic paintings and drawings by Turner to protect Turner's posthumous reputation. Ruskin's friend Ralph Nicholson Wornum, who was Keeper of the National Gallery, was said to have colluded in the alleged destruction of Turner's works. In 2005, these works, which form part of the Turner Bequest held at Tate Britain, were re-appraised by Turner Curator Ian Warrell, who concluded that Ruskin and Wornum had not destroyed them.

Since 2000, scholarly research has focused on aspects of Ruskin's legacy, including his impact on the sciences; John Lubbock and Oliver Lodge admired him. Two major academic projects have looked at Ruskin and cultural tourism (investigating, for example, Ruskin's links with Thomas Cook); the other focuses on Ruskin and the theatre. The sociologist and media theorist David Gauntlett argues that Ruskin's notions of craft can be felt today in online communities such as YouTube and throughout Web 2.0. Similarly, architectural theorist Lars Spuybroek has argued that Ruskin's understanding of the Gothic as a combination of two types of variation, rough savageness and smooth changefulness, opens up a new way of thinking leading to digital and so-called parametric design.

He was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century and up to the First World War. After a period of relative decline, his reputation has steadily improved since the 1960s with the publication of numerous academic studies of his work. Today, his ideas and concerns are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in environmentalism, sustainability and craft.

Before Ruskin began Modern Painters, John James Ruskin had begun collecting watercolours, including works by Samuel Prout and Turner. Both painters were among occasional guests of the Ruskins at Herne Hill, and 163 Denmark Hill (demolished 1947) to which the family moved in 1842.

Brantwood was opened in 1934 as a memorial to Ruskin and remains open to the public today. The Guild of St George continues to thrive as an educational charity, and has an international membership. The Ruskin Society organises events throughout the year. A series of public celebrations of Ruskin's multiple legacies took place in 2000, on the centenary of his death, and events are planned throughout 2019, to mark the bicentenary of his birth.

The centenary of Ruskin's birth was keenly celebrated in 1919, but his reputation was already in decline and sank further in the fifty years that followed. The contents of Ruskin's home were dispersed in a series of sales at auction, and Brantwood itself was bought in 1932 by the educationist and Ruskin enthusiast, collector and memorialist, John Howard Whitehouse.

Ruskin wrote over 250 works, initially art criticism and history, but expanding to cover topics ranging over science, geology, ornithology, literary criticism, the environmental effects of pollution, mythology, travel, political economy and social reform. After his death Ruskin's works were collected in the 39-volume "Library Edition", completed in 1912 by his friends Edward Tyas Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. The range and quantity of Ruskin's writing, and its complex, allusive and associative method of expression, cause certain difficulties. In 1898, John A. Hobson observed that in attempting to summarise Ruskin's thought, and by extracting passages from across his work, "the spell of his eloquence is broken". Clive Wilmer has written, further, that, "The anthologising of short purple passages, removed from their intended contexts [... is] something which Ruskin himself detested and which has bedevilled his reputation from the start." Nevertheless, some aspects of Ruskin's theory and criticism require further consideration.

Although Ruskin's 80th birthday was widely celebrated in 1899 (various Ruskin societies presenting him with an elaborately illuminated congratulatory address), Ruskin was scarcely aware of it. He died at Brantwood from influenza on 20 January 1900 at the age of 80. He was buried five days later in the churchyard at Coniston, according to his wishes. As he had grown weaker, suffering prolonged bouts of mental illness, he had been looked after by his second cousin, Joan(na) Severn (formerly "companion" to Ruskin's mother) and she and her family inherited his estate. Joanna's Care was the eloquent final chapter of Ruskin's memoir, which he dedicated to her as a fitting tribute.

A number of utopian socialist Ruskin Colonies attempted to put his political ideals into practice. These communities included Ruskin, Florida, Ruskin, British Columbia and the Ruskin Commonwealth Association, a colony in Dickson County, Tennessee in existence from 1894 to 1899.

In a letter to his physician John Simon on 15 May 1886, Ruskin wrote:

His last great work was his autobiography, Praeterita (1885–89) (meaning, 'Of Past Things'), a highly personalised, selective, eloquent but incomplete account of aspects of his life, the preface of which was written in his childhood nursery at Herne Hill.

The following description of Ruskin as a lecturer was written by an eyewitness, who was a student at the time (1884):

In principle, Ruskin worked out a scheme for different grades of "Companion", wrote codes of practice, described styles of dress and even designed the Guild's own coins. Ruskin wished to see St George's Schools established, and published various volumes to aid its teaching (his Bibliotheca Pastorum or Shepherd's Library), but the schools themselves were never established. (In the 1880s, in a venture loosely related to the Bibliotheca, he supported Francesca Alexander's publication of some of her tales of peasant life.) In reality, the Guild, which still exists today as a charitable education trust, has only ever operated on a small scale.

In 1879, Ruskin resigned from Oxford, but resumed his Professorship in 1883, only to resign again in 1884. He gave his reason as opposition to vivisection, but he had increasingly been in conflict with the University authorities, who refused to expand his Drawing School. He was also suffering from increasingly poor health.

In middle age, and at his prime as a lecturer, Ruskin was described as slim, perhaps a little short, with an aquiline nose and brilliant, piercing blue eyes. Often sporting a double-breasted waistcoat, a high collar and, when necessary, a frock coat, he also wore his trademark blue neckcloth. From 1878 he cultivated an increasingly long beard, and took on the appearance of an "Old Testament" prophet.

Although in 1877 Ruskin said that in 1860, "I gave up my art work and wrote Unto This Last ... the central work of my life" the break was not so dramatic or final. Following his crisis of faith, and influenced in part by his friend Thomas Carlyle (whom he had first met in 1850), Ruskin shifted his emphasis in the late 1850s from art towards social issues. Nevertheless, he continued to lecture on and write about a wide range of subjects including art and, among many other matters, geology (in June 1863 he lectured on the Alps), art practice and judgement (The Cestus of Aglaia), botany and mythology (Proserpina and The Queen of the Air). He continued to draw and paint in watercolours, and to travel extensively across Europe with servants and friends. In 1868, his tour took him to Abbeville, and in the following year he was in Verona (studying tombs for the Arundel Society) and Venice (where he was joined by William Holman Hunt). Yet increasingly Ruskin concentrated his energies on fiercely attacking industrial capitalism, and the utilitarian theories of political economy underpinning it. He repudiated his sometimes grandiloquent style, writing now in plainer, simpler language, to communicate his message straightforwardly.

The Guild's most conspicuous and enduring achievement was the creation of a remarkable collection of art, minerals, books, medieval manuscripts, architectural casts, coins and other precious and beautiful objects. Housed in a cottage museum high on a hill in the Sheffield district of Walkley, it opened in 1875, and was curated by Henry and Emily Swan. Ruskin had written in Modern Painters III (1856) that, "the greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and to tell what it saw in a plain way." Through the Museum, Ruskin aimed to bring to the eyes of the working man many of the sights and experiences otherwise reserved for those who could afford to travel across Europe. The original Museum has been digitally recreated online. In 1890, the Museum relocated to Meersbrook Park. The collection is now on display at Sheffield's Millennium Gallery.

Most controversial, from the point of view of the University authorities, spectators and the national press, was the digging scheme on Ferry Hinksey Road at North Hinksey, near Oxford, instigated by Ruskin in 1874, and continuing into 1875, which involved undergraduates in a road-mending scheme. The scheme was motivated in part by a desire to teach the virtues of wholesome manual labour. Some of the diggers, who included Oscar Wilde, Alfred Milner and Ruskin's future secretary and biographer W. G. Collingwood, were profoundly influenced by the experience: notably Arnold Toynbee, Leonard Montefiore and Alexander Robertson MacEwen. It helped to foster a public service ethic that was later given expression in the university settlements, and was keenly celebrated by the founders of Ruskin Hall, Oxford.

In 1871, John Ruskin founded his own art school at Oxford, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. It was originally accommodated within the Ashmolean Museum but now occupies premises on High Street. Ruskin endowed the drawing mastership with £5000 of his own money. He also established a large collection of drawings, watercolours and other materials (over 800 frames) that he used to illustrate his lectures. The School challenged the orthodox, mechanical methodology of the government art schools (the "South Kensington System").

Ruskin turned to spiritualism. He attended seances at Broadlands, which he believed gave him the ability to communicate with the dead Rose, which, in turns, both comforted and disturbed him. Ruskin's increasing need to believe in a meaningful universe and a life after death, both for himself and his loved ones, helped to revive his Christian faith in the 1870s.

Ruskin was unanimously appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in August 1869, largely through the offices of his friend, Henry Acland. He delivered his inaugural lecture on his 51st birthday in 1870, at the Sheldonian Theatre to a larger-than-expected audience. It was here that he said, "The art of any country is the exponent of its social and political virtues." It has been claimed that Cecil Rhodes cherished a long-hand copy of the lecture, believing that it supported his own view of the British Empire.

The lectures that comprised Sesame and Lilies (published 1865), delivered in December 1864 at the town halls at Rusholme and Manchester, are essentially concerned with education and ideal conduct. "Of Kings' Treasuries" (in support of a library fund) explored issues of reading practice, literature (books of the hour vs. books of all time), cultural value and public education. "Of Queens' Gardens" (supporting a school fund) focused on the role of women, asserting their rights and duties in education, according them responsibility for the household and, by extension, for providing the human compassion that must balance a social order dominated by men. This book proved to be one of Ruskin's most popular, and was regularly awarded as a Sunday School prize. Its reception over time, however, has been more mixed, and twentieth-century feminists have taken aim at "Of Queens' Gardens" in particular, as an attempt to "subvert the new heresy" of women's rights by confining women to the domestic sphere. Although indeed subscribing to the Victorian belief in "separate spheres" for men and women, Ruskin was however unusual in arguing for parity of esteem, a case based on his philosophy that a nation's political economy should be modelled on that of the ideal household.

John James had hoped to practise law, and was articled as a clerk in London. His father, John Thomas Ruskin, described as a grocer (but apparently an ambitious wholesale merchant), was an incompetent businessman. To save the family from bankruptcy, John James, whose prudence and success were in stark contrast to his father, took on all debts, settling the last of them in 1832. John James and Margaret were engaged in 1809, but opposition to the union from John Thomas, and the problem of his debts, delayed the couple's wedding. They finally married, without celebration, in 1818. John James died on 3 March 1864 and is buried in the churchyard of St John the Evangelist, Shirley, Croydon.

Ruskin's next work on political economy, redefining some of the basic terms of the discipline, also ended prematurely, when Fraser's Magazine, under the editorship of James Anthony Froude, cut short his Essays on Political Economy (1862–63) (later collected as Munera Pulveris (1872)). Ruskin further explored political themes in Time and Tide (1867), his letters to Thomas Dixon, a cork-cutter in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear who had a well-established interest in literary and artistic matters. In these letters, Ruskin promoted honesty in work and exchange, just relations in employment and the need for co-operation.

Ruskin was an art-philanthropist: in March 1861 he gave 48 Turner drawings to the Ashmolean in Oxford, and a further 25 to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge in May. Ruskin's own work was very distinctive, and he occasionally exhibited his watercolours: in the United States in 1857–58 and 1879, for example; and in England, at the Fine Art Society in 1878, and at the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolour (of which he was an honorary member) in 1879. He created many careful studies of natural forms, based on his detailed botanical, geological and architectural observations. Examples of his work include a painted, floral pilaster decoration in the central room of Wallington Hall in Northumberland, home of his friend Pauline Trevelyan. The stained glass window in the Little Church of St Francis Funtley, Fareham, Hampshire is reputed to have been designed by him. Originally placed in the St. Peter's Church Duntisbourne Abbots near Cirencester, the window depicts the Ascension and the Nativity.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters V (1860): Ruskin, Cook and Wedderburn, 7.422–423.

From 1859 until 1868, Ruskin was involved with the progressive school for girls at Winnington Hall in Cheshire. A frequent visitor, letter-writer, and donor of pictures and geological specimens to the school, Ruskin approved of the mixture of sports, handicrafts, music and dancing encouraged by its principal, Miss Bell. The association led to Ruskin's sub-Socratic work, The Ethics of the Dust (1866), an imagined conversation with Winnington's girls in which he cast himself as the "Old Lecturer". On the surface a discourse on crystallography, it is a metaphorical exploration of social and political ideals. In the 1880s, Ruskin became involved with another educational institution, Whitelands College, a training college for teachers, where he instituted a May Queen festival that endures today. (It was also replicated in the 19th century at the Cork High School for Girls.) Ruskin also bestowed books and gemstones upon Somerville College, one of Oxford's first two women's colleges, which he visited regularly, and was similarly generous to other educational institutions for women.

Ruskin gave the inaugural address at the Cambridge School of Art in 1858, an institution from which the modern-day Anglia Ruskin University has grown. In The Two Paths (1859), five lectures given in London, Manchester, Bradford and Tunbridge Wells, Ruskin argued that a 'vital law' underpins art and architecture, drawing on the labour theory of value. (For other addresses and letters, Cook and Wedderburn, vol. 16, pp. 427–87.) The year 1859 also marked his last tour of Europe with his ageing parents, during which they visited Germany and Switzerland.

During this period Ruskin wrote regular reviews of the annual exhibitions at the Royal Academy under the title Academy Notes (1855–59, 1875). They were highly influential, capable of making or breaking reputations. The satirical magazine Punch published the lines (24 May 1856), "I paints and paints,/hears no complaints/And sells before I'm dry,/Till savage Ruskin/He sticks his tusk in/Then nobody will buy."

Ruskin continued to support Hunt and Rossetti. He also provided an annuity of £150 in 1855–57 to Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti's wife, to encourage her art (and paid for the services of Henry Acland for her medical care). Other artists influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites also received both critical and financial support from Ruskin, including John Brett, John William Inchbold, and Edward Burne-Jones, who became a good friend (he called him "Brother Ned"). His father's disapproval of such friends was a further cause of considerable tension between them.

The marriage was unhappy, with Ruskin reportedly being cruel to Effie and distrustful of her. The marriage was never consummated and was annulled in 1854.

Although critics were slow to react and the reviews were mixed, many notable literary and artistic figures were impressed with the young man's work, including Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell. Suddenly Ruskin had found his métier, and in one leap helped redefine the genre of art criticism, mixing a discourse of polemic with aesthetics, scientific observation and ethics. It cemented Ruskin's relationship with Turner. After the artist died in 1851, Ruskin catalogued nearly 20,000 sketches that Turner gave to the British nation.

The Museum was part of a wider plan to improve science provision at Oxford, something the University initially resisted. Ruskin's first formal teaching role came about in the mid-1850s, when he taught drawing classes (assisted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) at the Working Men's College, established by the Christian socialists, Frederick James Furnivall and Frederick Denison Maurice. Although Ruskin did not share the founders' politics, he strongly supported the idea that through education workers could achieve a crucially important sense of (self-)fulfilment. One result of this involvement was Ruskin's Elements of Drawing (1857). He had taught several women drawing, by means of correspondence, and his book represented both a response and a challenge to contemporary drawing manuals. The WMC was also a useful recruiting ground for assistants, on some of whom Ruskin would later come to rely, such as his future publisher, George Allen.

Their early life together was spent at 31 Park Street, Mayfair, secured for them by Ruskin's father (later addresses included nearby 6 Charles Street, and 30 Herne Hill). Effie was too unwell to undertake the European tour of 1849, so Ruskin visited the Alps with his parents, gathering material for the third and fourth volumes of Modern Painters. He was struck by the contrast between the Alpine beauty and the poverty of Alpine peasants, stirring his increasingly sensitive social conscience.

During 1847, Ruskin became closer to Effie Gray, the daughter of family friends. It was for her that Ruskin had written The King of the Golden River. The couple were engaged in October. They married on 10 April 1848 at her home, Bowerswell, in Perth, once the residence of the Ruskin family. It was the site of the suicide of John Thomas Ruskin (Ruskin's grandfather). Owing to this association and other complications, Ruskin's parents did not attend. The European Revolutions of 1848 meant that the newlyweds' earliest travels together were restricted, but they were able to visit Normandy, where Ruskin admired the Gothic architecture.

Drawing on his travels, he wrote the second volume of Modern Painters (published April 1846). The volume concentrated on Renaissance and pre-Renaissance artists rather than on Turner. It was a more theoretical work than its predecessor. Ruskin explicitly linked the aesthetic and the divine, arguing that truth, beauty and religion are inextricably bound together: "the Beautiful as a gift of God". In defining categories of beauty and imagination, Ruskin argued that all great artists must perceive beauty and, with their imagination, communicate it creatively by means of symbolic representation. Generally, critics gave this second volume a warmer reception, although many found the attack on the aesthetic orthodoxy associated with Joshua Reynolds difficult to accept. In the summer, Ruskin was abroad again with his father, who still hoped his son might become a poet, even poet laureate, just one among many factors increasing the tension between them.

Ruskin toured the continent with his parents again in 1844, visiting Chamonix and Paris, studying the geology of the Alps and the paintings of Titian, Veronese and Perugino among others at the Louvre. In 1845, at the age of 26, he undertook to travel without his parents for the first time. It provided him with an opportunity to study medieval art and architecture in France, Switzerland and especially Italy. In Lucca he saw the Tomb of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia, which Ruskin considered the exemplar of Christian sculpture (he later associated it with the then object of his love, Rose La Touche). He drew inspiration from what he saw at the Campo Santo in Pisa, and in Florence. In Venice, he was particularly impressed by the works of Fra Angelico and Giotto in St Mark's Cathedral, and Tintoretto in the Scuola di San Rocco, but he was alarmed by the combined effects of decay and modernisation on the city: "Venice is lost to me", he wrote. It finally convinced him that architectural restoration was destruction, and that the only true and faithful action was preservation and conservation.

Ruskin first came to widespread attention with the first volume of Modern Painters (1843), an extended essay in defence of the work of J. M. W. Turner in which he argued that the principal role of the artist is "truth to nature". From the 1850s, he championed the Pre-Raphaelites, who were influenced by his ideas. His work increasingly focused on social and political issues. Unto This Last (1860, 1862) marked the shift in emphasis. In 1869, Ruskin became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, where he established the Ruskin School of Drawing. In 1871, he began his monthly "letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain", published under the title Fors Clavigera (1871–1884). In the course of this complex and deeply personal work, he developed the principles underlying his ideal society. As a result, he founded the Guild of St George, an organisation that endures today.

Ruskin's health was poor and he never became independent from his family during his time at Oxford. His mother took lodgings on High Street, where his father joined them at weekends. He was devastated to hear that his first love, Adèle Domecq, the second daughter of his father's business partner, had become engaged to a French nobleman. In April 1840, whilst revising for his examinations, he began to cough blood, which led to fears of consumption and a long break from Oxford travelling with his parents.

His most noteworthy success came in 1839 when, at the third attempt, he won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for poetry (Arthur Hugh Clough came second). He met William Wordsworth, who was receiving an honorary degree, at the ceremony.

From September 1837 to December 1838, Ruskin's The Poetry of Architecture was serialised in Loudon's Architectural Magazine, under the pen name "Kata Phusin" (Greek for "According to Nature"). It was a study of cottages, villas, and other dwellings centred on a Wordsworthian argument that buildings should be sympathetic to their immediate environment and use local materials. It anticipated key themes in his later writings. In 1839, Ruskin's "Remarks on the Present State of Meteorological Science" was published in Transactions of the Meteorological Society.

In Michaelmas 1836, Ruskin matriculated at the University of Oxford, taking up residence at Christ Church in January of the following year. Enrolled as a gentleman-commoner, he enjoyed equal status with his aristocratic peers. Ruskin was generally uninspired by Oxford and suffered bouts of illness. Perhaps the greatest advantage of his time there was in the few, close friendships he made. His tutor, the Rev Walter Lucas Brown, always encouraged him, as did a young senior tutor, Henry Liddell (later the father of Alice Liddell) and a private tutor, the Rev Osborne Gordon. He became close to the geologist and natural theologian, William Buckland. Among his fellow-undergraduates, Ruskin's most important friends were Charles Thomas Newton and Henry Acland.

Ruskin was greatly influenced by the extensive and privileged travels he enjoyed in his childhood. It helped to establish his taste and augmented his education. He sometimes accompanied his father on visits to business clients at their country houses, which exposed him to English landscapes, architecture and paintings. Family tours took them to the Lake District (his first long poem, Iteriad, was an account of his tour in 1830) and to relatives in Perth, Scotland. As early as 1825, the family visited France and Belgium. Their continental tours became increasingly ambitious in scope: in 1833 they visited Strasbourg, Schaffhausen, Milan, Genoa and Turin, places to which Ruskin frequently returned. He developed a lifelong love of the Alps, and in 1835 visited Venice for the first time, that 'Paradise of cities' that provided the subject and symbolism of much of his later work.

Ruskin's journeys also provided inspiration for writing. His first publication was the poem "On Skiddaw and Derwent Water" (originally entitled "Lines written at the Lakes in Cumberland: Derwentwater" and published in the Spiritual Times) (August 1829). In 1834, three short articles for Loudon's Magazine of Natural History were published. They show early signs of his skill as a close "scientific" observer of nature, especially its geology.

Ruskin's childhood was spent from 1823 at 28 Herne Hill (demolished c. 1912 ), near the village of Camberwell in South London. He had few friends of his own age, but it was not the friendless and toyless experience he later claimed it was in his autobiography, Praeterita (1885–89). He was educated at home by his parents and private tutors, and from 1834 to 1835 he attended the school in Peckham run by the progressive evangelical Thomas Dale (1797–1870). Ruskin heard Dale lecture in 1836 at King's College, London, where Dale was the first Professor of English Literature. Ruskin went on to enroll and complete his studies at King's College, where he prepared for Oxford under Dale's tutelage.

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900) was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, as well as an art patron, draughtsman, watercolourist, philosopher, prominent social thinker and philanthropist. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and political economy.

Before he returned to Oxford, Ruskin responded to a challenge that had been put to him by Effie Gray, whom he later married: the twelve-year-old Effie had asked him to write a fairy story. During a six-week break at Leamington Spa to undergo Dr Jephson's (1798–1878) celebrated salt-water cure, Ruskin wrote his only work of fiction, the fable The King of the Golden River (not published until December 1850 (but imprinted 1851), with illustrations by Richard Doyle). A work of Christian sacrificial morality and charity, it is set in the Alpine landscape Ruskin loved and knew so well. It remains the most translated of all his works. Back at Oxford, in 1842 Ruskin sat for a pass degree, and was awarded an uncommon honorary double fourth-class degree in recognition of his achievements.

Ruskin was the only child of first cousins. His father, John James Ruskin (1785–1864), was a sherry and wine importer, founding partner and de facto business manager of Ruskin, Telford and Domecq (see Allied Domecq). John James was born and brought up in Edinburgh, Scotland, to a mother from Glenluce and a father originally from Hertfordshire. His wife, Margaret Cock (1781–1871), was the daughter of a publican in Croydon. She had joined the Ruskin household when she became companion to John James's mother, Catherine.

Millais had painted Effie for The Order of Release, 1746, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852. Suffering increasingly from physical illness and acute mental anxiety, Effie was arguing fiercely with her husband and his intense and overly protective parents, and sought solace with her own parents in Scotland. The Ruskin marriage was already fatally undermined as she and Millais fell in love, and Effie left Ruskin, causing a public scandal.